Writers In Times of War - The Duty To Disrupt

Current Events

|

Jul 19, 2018

|

6 MIN READ

“What does your tattoo say?” I asked the girl at the register. She is black and is wearing a small silver cross around her neck. She looked at her forearm before responding, in the way people do when you compliment something on their person, as if they have to remind themselves what they're wearing to accept what you said.

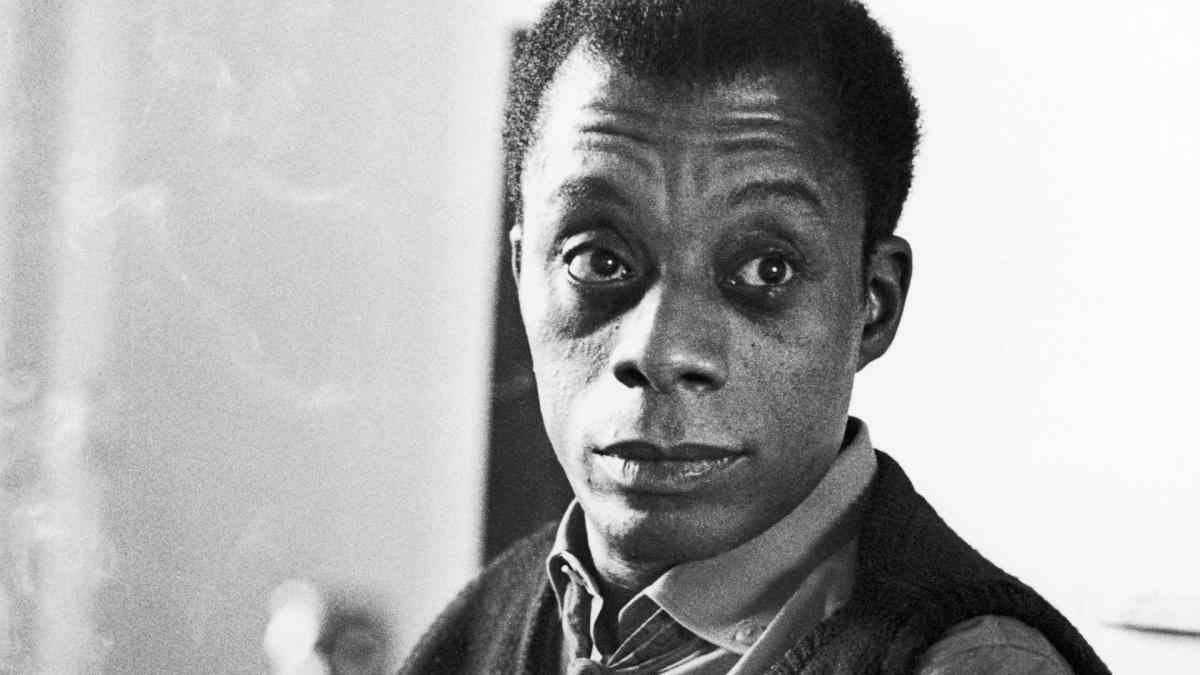

I don't remember the quote she recited, but I nodded in the small pause before she said, “it’s a Baldwin quote.”

I was disappointed I hadn't known that myself, and impressed that she knew Baldwin because she looked so young, 18 or 19 at most. For whatever reason, I always measured up young people by what they know at their age and compared it to what I knew at the same age. I heard of Baldwin in my second or third year of college. But then that was because I was in gender studies and our department sometimes tried to be intersectional – otherwise, I was mostly reading British literature by Austen, Woolf, and Forester.

“That’s awesome,” I said, “I love his work.”

“I know! I’m glad you know him. People always ask me what it says, but then when I say it’s a Baldwin quote they ask who he is.”

“Wait seriously—like in this job?”

I expected people who frequented Barnes and noble, at least those in their 20s and 30s, to know Baldwin.

“Wait,” I started again excitedly, “have you seen the documentary?”

“I Am Not Your Negro? Yes. This quote is actually from it.”

“Really? I loved that documentary, it was such an emotional experience for me – like I have never watched a movie that made me feel so empowered but also left me so changed.”

“Yeah. Me too. When I finished watching it I said I have to find a way to document this moment, so I went and got this tattoo.”

She put my Moleskine and my receipt in the bag, and we said our goodbyes.

My interactions with Baldwin before the documentary were only brushes – reverential references made to him in lectures and works of literature on black feminism and the Black Lives Matter movement that made it very clear his was a household name I should be embarrassed not to know. Still, I didn’t read his work in any meaningful way then. I sufficed to know his name and appreciate the elusive allusions to a great writer of the 50s, 60s and 70s (already a romanticized period in my mind) who left America to live in Paris, who visited Shakespeare & Co., a bookstore I had become obsessed with reading about, and writer who lived the romanticized trope of the writer’s life. The life I had wanted to live since I decided I wanted to be a writer in 3rd grade.

I was brought up in a political family. Growing up, my parents spoke a lot about their college experiences and their Islamic and anti-imperialist activism. My mother and I always watched period dramas and films set during one of the world wars or in the post-colonial era. I wanted to live like the revolutionary young people I was surrounded with, and I wanted to create art that fueled revolutions. In my romantic delusions about what it meant to be a writer in a time of war, I always imagined myself and my revolutionary friends and the man I might marry in scene, paving the long and harsh road to liberty.

But as I grew older, this romanticization gave way to the devastating reality of modern and contemporary Arab and Muslim history. I had spent much of my childhood reading about Muslim rulers and inventions, Muslim wealth and empire, and scientific advancements and anti-colonialism. I had watched animated films and documentaries the very soundtracks of which made my chest swell with pride. But, as a 90’s kid, it became increasingly difficult to match up that history with my reality. For my brother, who was born in 2001, he has never known an America not at war with Muslims. His whole life, and much of mine, has been defined by Muslim and Arab failure: over and over again. There was one year of respite: in 2011 when the Arab revolts took place across much of the Arab world. I wrote stories and poems, wore themed t-shirts, read the appropriate poetry, posted status after status, memorized songs, waved flags, hung photos on walls and doors. And then, when the revolts failed, I dropped politics like hot coal. Art and writing became a refuge from wartime and failed activism, instead of a comment on or reflection of them, and an escape from the constant need to prove the value of my people’s existence and expose the evils of capitalism and imperialism and sexism and racism. I stopped reading dystopian and historical fiction, or anything that focused on war and revolution. But it is difficult to ignore the world falling apart around me.

All the hope to relive my parents’ glory days and be a part of something quickly evaporated when Morsi was overthrown and Sisi took hundreds of political prisoners, Bashar killed hundreds of thousands mercilessly, the movement in Jordan was shut down, and the list of political failures my people experienced only got longer.

And then the dark heart of America became even more obvious to me when Trump won the presidential elections in 2017. I didn’t really think he would – I thought most Americans would vote Hillary to give themselves a pat on the back for being liberal enough to elect a woman even if many of them were classist, racist, sexist, and Islamophobic imperialists. Just after his election, in one of my classes, a friend said something about not being political and resigning himself to a Walden-like place until this all blew over, and, while I sympathized with him because I had become so disillusioned with politics, I also anticipated what my Arab friend said to him next: “Don’t say you’re not political. Everyone is political. You just have the privilege not to care about politics because you’re not affected in the same way.” What she said is true – but not just for our white-ish friend. It was true for me too because even if I am a person of color, and a Muslim, and a woman, and not particularly well off, I can still somehow afford to turn my back on the issues and use disillusionment as an excuse to avoid addressing the political. But it cannot be an option – only to witness and not write the story that erupts from the violence of war and imperialism. “Can I merely be a witness?” Albert Camus asks, “In other words: have I the right to be merely an artist? I cannot believe so.” he says.

Nor can I.

...

I remember when I went to watch the Baldwin documentary, I Am Not Your Negro. There were 7 other people in the theatre with me. Everyone was black except me and an elderly white man. I cried a lot during the film, and was proud when Malcolm X came on the screen, honored by the fact that me and this man shared a religion, because he gave me a reason to feel like I had any connection to the tremendous tradition of struggle for liberty and equality that I otherwise felt entitled only to admire from a distance. This, I thought to myself, while listening to the words of Baldwin as he illustrated the lives of Dr. King, Brother Malcolm and Medgar Evers and linked them in different literary forms and styles to the larger struggle for civil rights and liberty – seamlessly weaving in and out of thought, reality, social memory, and the human imagination. This is what writing is supposed to do. In an interview in 1961, Baldwin said, “It is true that the nature of society is to create, among its citizens, an illusion of safety; but it is also absolutely true that the safety is always necessarily an illusion. Artists are here to disturb the peace.”

The responsibility and the burden to witness, reflect, reinforce, and bring to light the struggle is heavier than I want to bear sometimes, but it exists, and it won’t disappear no matter how many of us refuse to take it on. But, it will become lighter – perhaps at some point so light that you will look up and realize that reality itself has changed.

This post was written by R.K. Almajali – one caffeine-obsessed book hoarder who dreams of opening up a literary cafe where people can pay at least half their bill in flowers and art. She (almost consistently) writes about women, relationships, language, grief, and how the personal is always political. She can be reached at r.k.almajali@gmail.com

Love this post? Don't be selfish - share it with your friends!

Subscribe to be the first to know about new product releases, styling ideas and more.

What products are you interested in?