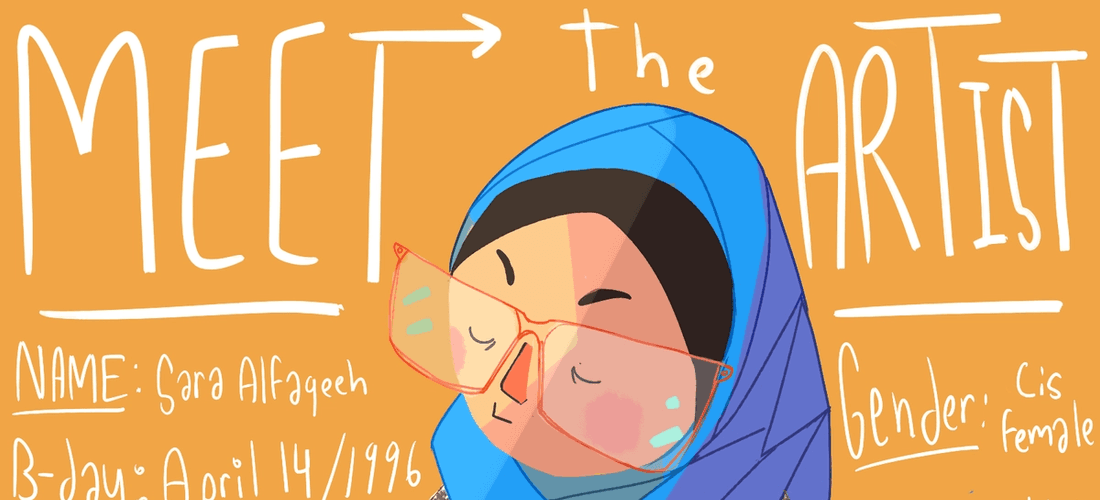

Sara Alfageeh on Comics & The Power of Positive Representation

Lifestyle

|

Aug 28, 2017

|

7 MIN READ

I’ve always loved visual storytelling, and this love eventually blossomed into a career as an illustrator and a cartoonist. Growing up, I spent a lot of my time trying to answer questions about representation, but now that I’m responsible for sharing my own stories, it's become even more important to me.

Long before I was drawing, I was spending my childhood running back and forth to the book store for volumes of Justice League, issues of Batman, Wonder Woman, Avengers, and all the X-Men that I could get. I would sit cross-legged on the floor of the graphic novel section and burn through stacks of comics taller than me every week. This was during the early 2000's when the Saturday morning cartoon blocks were back-to-back shows like Justice League, Static Shock and Batman Beyond. I couldn’t get enough. Although I was too young to understand it as a kid, I was pretty excluded from these same stories that I loved.

Storytelling is important because it’s how we empower and validate ourselves. Classic superhero stories are told with universal themes like “Good will always defeat Evil” and “The strong have a responsibility to defend the weak.” While these themes are important and universally relatable, the problem lies in how we’ve been representing the characters in these stories for decades in Western media. What is the effect when the figure of “good” is always a physically impressive white man who is above the normal law enforcement, or the figure for “weak” is a woman, or “evil” happens to always be a conniving foreigner? What happens to those in the audience who accept that they do not belong to the mainstream narrative and are not welcome to it? What other narratives are they forced to seek out instead?

I stress the importance of being able to visually identify with a protagonist you’re supposed to be rooting for. All young children need to be able to flip through a book, channel surf or see and a movie trailer and, at some point, say, “Hey, they look like me!”

Back to my story...This smaller nerd grew up to be a bigger nerd. If you don’t believe me, here are some pictures of me in my recent costumes after nine years of attending anime and comic cons. ;)

I was subconsciously trying to fill the gaps in my favorite media. As part of the audience realized that I was just going to be the representation I didn’t see, and finally ended up on the other end as an illustrator and creator. It’s like a geeky butterfly transformation!

So clearly, I was very much into it. But what do a bunch of men in spandex have to do with anything?

1) Comics are examples of literary storytelling. They are different than books and other forms of media because the writing is minimal and mostly consists of dialogue. It creates a more interpersonal interaction with what’s happening on the page.

2) The literary aspect works together with visual storytelling, where we’re connecting to colors and lines, and can dictate how to represent our world.

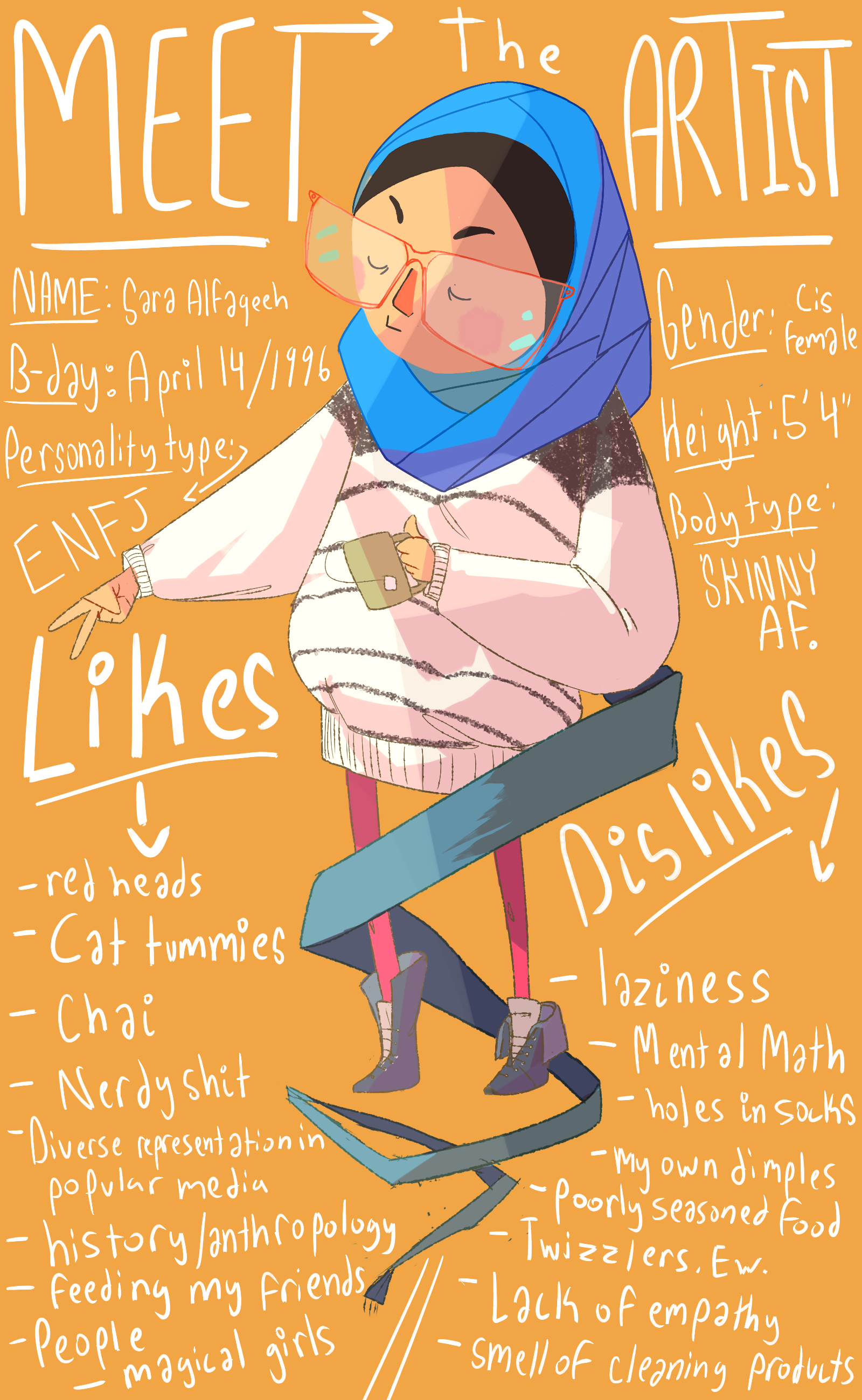

3) Comics influence pop culture. Our world is getting smaller due to mass communication technology; names like 'Superman' and 'Spiderman' are known in households on every continent.

4) Comics are the source for cinematic storytelling; a multi-billion-dollar entertainment industry spread across movies, shows, games, toys, clothes and more.

So, yeah. Comics are a big deal.

As a kid, I wanted to read comics. As an enthusiastic fan, I wanted to know who else out there was reading comics too. Now, I want to know who's behind them.

When I first started making my own art, I wanted to distance myself from creating anything about Muslim women. As a visibly Muslim woman myself, and a hijabi, I believed others expected me to always tie my work to my identity, and I found that concept incredibly frustrating and limiting. I knew that for many, my hijab reduced me to a caricature of half-truths and stereotypes and that there were people who decided how they wanted to act around me before I even interacted with them. Instead of challenging that with my own stories, I convinced myself that working without my identity was somehow more professional.

A few years later, I can easily say that this mindset was very toxic for me. After looking through the history of comics, I was able to break out of it. What’s different in mainstream comics is that power-fantasies are these literal tropes, and you can see that some of the most iconic characters in pop culture were the power fantasies of their authors.

For example, Jerry Seigal and Joe Schuster published Superman in Action Comics in 1938. Two poor, Jewish men ended up making one of the most internationally recognized fictional characters, with a face and story still known over 70 years later. Superman was the extension of those wishing to escape the reality of Depression-era United States.

Joe Simon and Jack Kirby made Captain America in 1941 as a fictional response to World War II. Again, it was poor Jewish men creating a timeless icon. They couldn’t punch Hitler, but Captain America could. Simon and Kirby were making unapologetic, strong political and social stances, considering the issue dropped before the U.S. entered World War II.

Luke Cage was the first Black title character created by Archie Goodwin and John Romita Sr. Issue #1 of Hero for Hire appeared in the summer of 1972; he had distinctly unbreakable, bulletproof skin, which was no coincidence after the height of the Civil Rights movement.

Men have been using comics to explore their power-fantasies for over 70 years and created an entire industry out of it. In the pages of comics, these protagonists were morally good and stood up for what they believed in; they were physically ideal, their enemies were easy to spot and undeniably evil, and at the end of the day, they got the girl. There was nothing a man couldn’t do. A woman on the other hand? That was a little trickier.

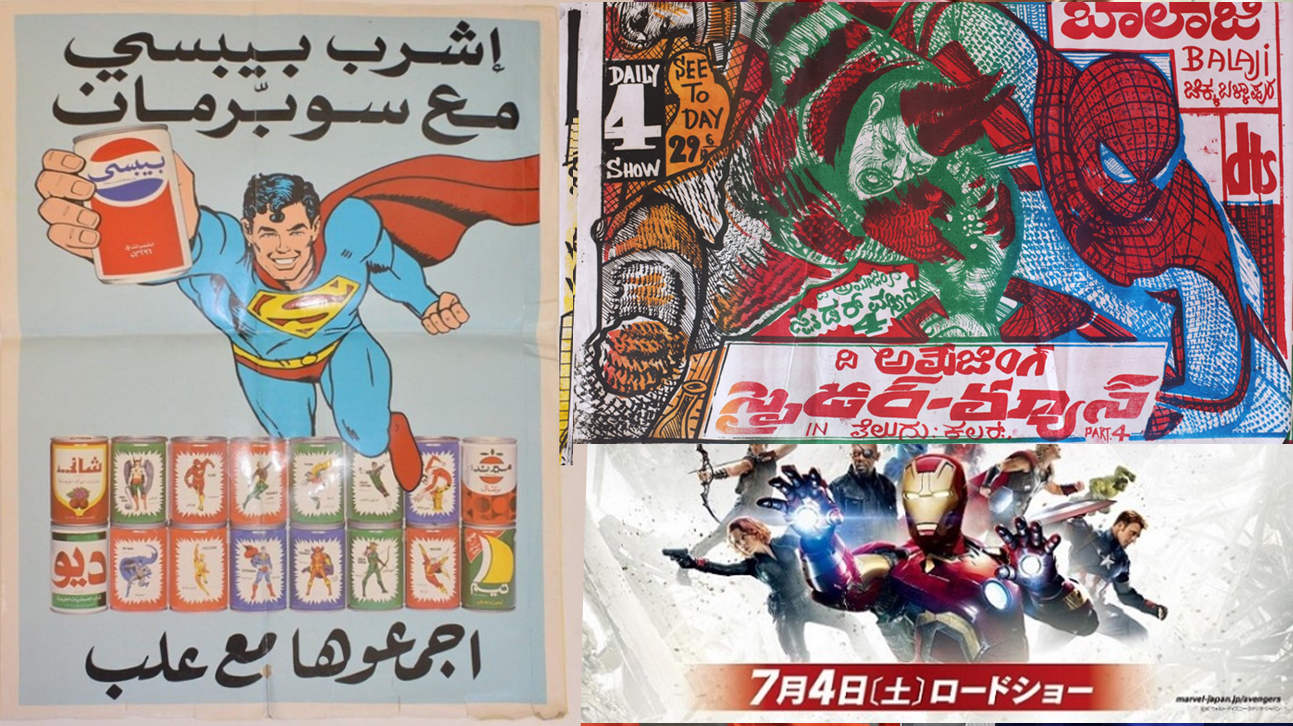

Today, a comic written by Muslim women is the top-selling comic at Marvel, one of the two biggest comic publishers of all time. The first issue has so far been reprinted seven times and even topped digital sales too! At one point, Issue #1 was the most downloaded digital single issue at Marvel. I had never experienced anything like that before — being able to see a character I identified with accepted into the mainstream like that — and to be honest, I never expected myself to. That’s what happens when you grow up never being allowed to be the hero.

I used to want to distance myself from my identity in my artwork because I was convinced it was all people expected me to be good for. In reality, it was because I had never witnessed successful positive representation. As a woman, I was told not to take up space. As a Muslim in the U.S., I was told not to attract further attention to myself.

Ms. Marvel changed that for me.

I only wish that I could have seen Kamala Khan as a kid, but what’s more important is that she and other protagonists are here for young girls now. The stories are changing as there are new authors and new audiences who are seeking out the narratives that haven’t been given their chance yet. Social media, streaming sites like YouTube, and online crowd funding have put the power into the hands of individual creators, and have forever changed the landscape of how we can access stories. How do you prove you are a part of a culture unless you’re contributing to it?

Please make your art, because your stories deserve to be told — if not for you, then for the 10-year-old girl sitting cross legged on the floor of a library, looking through stacks of comics, but never finding herself in them.

You can check out more of Sara’s art portfolio or follow her on Twitter @thefoofinator.

Why does representation in art matter to you? Let us know in the comments below, and be sure to check out Sara's Kickstarter campaign and show some support!

And don't be selfish - if you like this post, share it!

Subscribe to be the first to know about new product releases, styling ideas and more.

What products are you interested in?